By Cristian Morales, for the Summer 2023 SKAT Newsletter

The 50th anniversary edition of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions opens with an introductory essay by Ian Hacking, with the first line he writes reading “Great books are rare. This is one. Read it and you will see.” and his final line reading “… [this] book really did change ‘the image of science by which we are now possessed.’ Forever.” Although he of course only had Kuhn’s seminal work in mind when writing this, it is also quite fair to say that these words aptly describe Hacking and his scholarship as well.

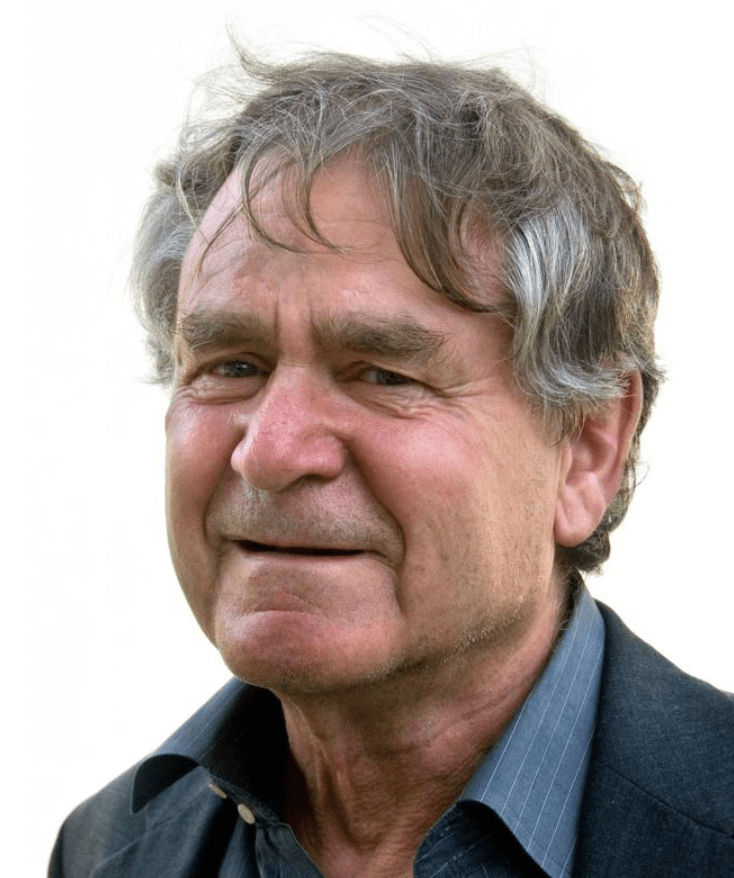

Ian MacDougall Hacking was born in 1936 in Vancouver, Canada, the only child of a father who managed cargo on freighter ships and a mother who was a milliner. He displayed his intellectual leanings from an early age, with his daughter Jane sharing that “when he was 3 or 4 years old, he would sit and read the dictionary… His parents were completely baffled.”

He earned his bachelor’s degree in 1956 from the University of British Columbia (UBC), and went on to earn his PhD from the University of Cambridge in 1962. He spent his early career moving between appointments at UBC, Cambridge, and Stanford University, before he returned again to his native country; his daughter Jane once saying “he was as Canadian as they come, and he never felt at home in the United States.” He spent almost two decades at the University of Toronto from 1983 to 2000, his academic home where he would write some of his most famous works, including Representing and Intervening (1983), The Taming of Chance (1990), Rewriting the Soul (1995), and Mad Travelers (1998). In 2000, he moved to the prestigious Collège de France in Paris, becoming the first Anglophone elected to a permanent chair in the

institution’s history, which he held until his retirement in 2006.

Often noted for the sheer breadth of his scholarship, Hacking made contributions to many disciplines, including the philosophies of science, physics, probability and mathematics, language, and psychology and psychiatry, across the 13 books and hundreds of articles he published during his career. Prof. Cheryl Misak, a colleague of Hacking’s at the University of Toronto, described him as “a one-person interdisciplinary department all by himself. Anthropologists, sociologists, historians and psychologists, as well as those working on probability theory and physics, took him to have important insights for their disciplines.”

His scholarship rightfully earned him a reputation as one of the world’s leading philosophers of science, and his work was recognized in 2002 with Canada’s first Killan Prize for the Humanities, and again in 2009 with the internationally-renowned Holberg Prize. In a description of his work for the latter award, Ragnar Fjelland and Roger Strand, of the University of Bergen, wrote: “In spite of this diversity [of scholarship] there is one regulative idea that pervades all his work: Science is a human enterprise. It is always created in a historical situation, and to understand why present science is as it is, it is not sufficient to know that it is “true”, or confirmed. We have to know the historical context of its emergence.”

Although so often described as an intellectual titan, those who knew Hacking often talked about his humility, generosity, and inquisitiveness. In a 2009 interview with a Canadian newspaper to highlight his receiving the Holberg Prize, Hacking began the interview, rather than talking about his work or award, by pointing out a wasp flying near a rose in his backyard garden and relating the scene to the physics principle of nonlocality: that everything in the universe is aware of everything else.

“That’s what you should be writing about,” he said. “Not me. I’m a dilettante. My governing word is ‘curiosity.’ … I would be very happy if you were to note that one of the features of me is that I’m curious.”